By Chaelee Benny (she/they)

This article contains discussions of misogyny, including structural and medical misogyny

This report will examine the structural inequalities in healthcare and socioeconomic status experienced by women in Australia. Focusing on employment levels and the underrepresentation of women’s health in research, this report explores the historical and ongoing patterns of structural inequality through the lens of male privilege and gender socialisation. Structural inequality is defined as the lack of control over societal power and the limitations that reinforce opportunities for certain groups while denying equitable access to others (Ball & Carpenter, 2019; Royce, 2022). The opportunities available to a person depend on factors such as gender, place of birth, and physical attributes (Berryessa, 2022). Male privilege refers to a patriarchal societal structure that awards unearned benefits to a dominant masculine social identity (Schwiter et al., 2021).

Income and Employment Levels

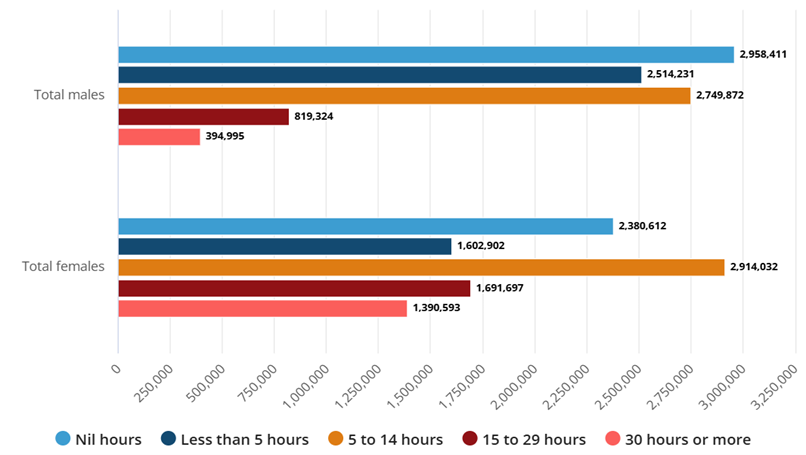

The theory of biological determinism asserts that children are exposed to gender roles and stereotypes based on their sex assigned at birth (Nyarko Ayisi & Krisztina, 2022). This belief fosters gender socialisation and can be observed through the division of labour between genders (Berryessa, 2022). Observing data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) censuses between 2006 and 2021, women have been significantly overrepresented in unpaid domestic labour annually (ABS, 2022). Unpaid domestic labour includes home maintenance, childcare, cooking, and additional non-financial support for a family (ABS, 2022). Averaging data from the ABS 2020-21 Time Use Survey, we can observe the significant gender disparity towards unpaid domestic labour, with 71.5% of women reporting their contributions compared to only 46.3% of men (ABS, 2022).

Furthermore, ABS employment surveys show that men are more likely to experience stable employment and income, with an average of 68.5% compared to 60.5% for women. The gender pay gap also results in men earning an average of $28,425 more per year through wages, bonuses, and superannuation. One contributing factor is the higher cultural and economic value placed on male-dominated STEM industries, which consistently pay more than female-dominated industries, such as teaching, childcare, and aged care. This structural valuation influences pay scales and career pathways, affording men greater access to higher-paid roles and reinforcing gendered economic inequality (WGEA, 2025; ABS, 2022).

Figure 1 Women’s and men’s hourly involvement in unpaid domestic work, 2021 Census, (ABS, 2022).

Continuing this trend, 53.7% of women aged 25 to 34 completed a bachelor’s degree or higher in May 2024, with only 58.7% of these female graduates able to obtain full-time employment in 2025. While only 40.8% of men aged 25-34 completed tertiary education, these graduates were overrepresented, with 77.5% of male graduates securing full-time employment in contrast with their female counterparts (ABS, 2025).

This data explains how social expectations materialise through the unequal responsibilities women face. These responsibilities include unpaid leave to look after family members, contributing significant time to domestic labour, and pursuing higher education in an attempt to increase employment opportunities. Statistically, men have greater opportunities and accessibility to both employment and income, whereas women face additional barriers and must invest greater effort to achieve the same level of success (Berryessa, 2022).

Gender essentialism assumes that binary gender is innate and absolute, and the roles of gender are strictly defined by ‘evolutionary’ biology (Fine, 2018). This framework dictates that childbearing capacity renders women instinctively maternal (Berryessa, 2022). Those assigned female at birth (AFAB) are socialised at a young age to believe that their bodies exist for reproduction and motherhood (Fox, 2023). This socialisation results in women playing a more significant role in unpaid domestic labour, affecting their ability to access secure employment and confining them to domestic roles by default (King, 2021; Delgado-Herrera et al., 2024).

Gender Disparity in Medical Research

The health of women and AFAB people has been historically under-researched and underfunded (Fox, 2023). As a result, there is a significant gap in knowledge and research into breast cancer, autoimmune diseases, gynaecology, pain, and mental ill-health. Current research and treatment reflect a medically biased perspective (Fox, 2023; Merone et al., 2022).

The 2022 ABS’s National Health and Mental Health Survey reported significant gender disparities in both physical and mental health conditions. More than half of women (52.3%) had one or more chronic conditions, compared to 47.4% of men. 13.04% of women were experiencing and/or being treated for psychological health conditions compared to 8.64% of men. Additionally, 21.6% of women used one or more mental health-related medications, compared to 13.5% of men, and 21.1% of women experienced anxiety disorders, compared to 13.3% of men. Similarly, rates of suicidal thoughts and behaviours were also elevated in women, 3.5%, compared to 3.1% (ABS, 2023).

Figure 2 Anxiety disorders in women from 2021 to 2022 (ABS, 2024).

Women experience higher rates of misdiagnosis and symptom dismissal due to a combination of structural biases in medical research and implicit bias in clinical decision-making (King, 2021). Historically, women’s health concerns have been trivialised or morally framed. For centuries, women’s pain, including childbirth, was interpreted as a divinely ordained punishment for Eve’s original sin, reinforcing the acceptance of women’s suffering as natural or expected (Corretti & Desai, 2018). This dismissal continued in medical settings, where conditions such as endometriosis were minimised as routine period pain, while multiple sclerosis was attributed to having a hysterical nature (Merone et al., 2022). Women and AFAB individuals were further excluded from clinical studies due to the assumption that their fluctuating hormones, menstrual cycles, and risk of pregnancy introduced irrelevant complexity, with the belief that the results in male participants could generalise treatment (Merone et al., 2022). Furthermore, women were assumed to be participating in caregiving responsibilities, therefore having limited availability for clinical trial involvement (Fox, 2023).

More recent evidence reinforces these inequities. The 2024 Victorian Inquiry into Women’s Pain documented widespread reports of dismissal, delayed diagnosis, and untreated symptoms, particularly in gynaecological and chronic pain contexts (Department of Health, Victoria, 2024). The unequal power dynamic that favours the male experience, despite women’s clear statistical outliers in health, supports a hierarchy that positions male health as inherently more significant and worthy of research.

The statistical findings from 2020 to 2024 referenced in this report highlight continuous inequalities experienced in healthcare and socioeconomic status for women in Australia. Disadvantage is observed in employment, health. Women hold substantial responsibilities in balancing domestic workload and childcare, as well as barriers to obtaining, maintaining, and advancing employment. Additionally, women must invest significant effort in finding non-stigmatising doctors due to the lack of structured answers to health complications that are comparatively promptly addressed in men.

Got a feminist opinion you want to share? We want to publish your work! Anyone can contribute to the GJP blog, no experience necessary! Find out more about being featured on our blog.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Gender indicators, current. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/gender-indicators

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Unpaid work and care: Census, 2021. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/unpaid-work-and-care-census/2021

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). Health conditions prevalence, 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/health-conditions-prevalence/2022

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2023). National study of mental health and wellbeing. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/2020-2022

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Education and Work, Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/education/education-and-work-australia/latest-release

Ball, M., & Carpenter, B. (2019). Justice in Society (2nd ed.). The Federation Press.

Berryessa, C. M. (2022). Losing the lottery of life: Examining intuitions of desert toward the socially and genetically “unlucky” in criminal punishment contexts. Behavioural Sciences & the Law, 40(3), 403–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2563

Corretti, C., & Desai, S. P. (2018). The Legacy of Eve’s Curse: Religion, Childbirth Pain, and the Rise of Anesthesia in Europe: c. 1200-1800s. Journal of Anesthesia History, 4(3), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janh.2018.03.009

Davey, M. (2021). “Gender ignorant” treasurers leave Australia lagging behind in women’s equality, equity advocate says. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jan/29/gender-ignorant-treasurers-leave-australia-lagging-behind-in-womens-equality-equity-advocate-says

Delgado-Herrera, M., Aceves-Gómez, A. C., & Reyes-Aguilar, A. (2024). Relationship between gender roles, motherhood beliefs and mental health. PLOS ONE, 19(3), 400–678. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0298750

Department of Health. Victoria, A. (2024). Inquiry into Women’s Pain. Www.health.vic.gov.au. https://www.health.vic.gov.au/inquiry-into-womens-pain

Fine, C. (2018). Testosterone Rex: myths of sex, science, and society. W.W. Norton.

Fox, M. (2023). Despite decades of promises, health research still overlooks women. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2023/nov/20/women-health-research-jill-biden-white-house

Harris, D., & Deal, H. (2018). Male privilege. Essential Library, An Imprint of Abdo Publishing.

King, M. (2021). Limiting potential from age 10: how girls pigeonhole themselves. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/jan/31/limiting-potential-from-age-10-how-girls-pigeonhole-themselves

Merone, L., Tsey, K., Russell, D., & Nagle, C. (2022). Sex Inequalities in Medical Research: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Literature. Women’s Health Reports, 3(1), 49–59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8812498/

Nyarko Ayisi, D., & Krisztina, T. (2022). Gender Roles and Gender Differences Dilemma: An Overview of Social and Biological Theories. Journal of Gender, Culture and Society, 2(1), 51–56. https://doi.org/10.32996/jgcs.2022.2.1.5

Ruppanner, L. (2022). Yet again, the census shows women are doing more housework. Now is the time to invest in interventions. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/yet-again-the-census-shows-women-are-doing-more-housework-now-is-the-time-to-invest-in-interventions-185488

Schwiter, K., Nentwich, J., & Keller, M. (2021). Male privilege revisited: How men in female‐dominated occupations notice and actively reframe privilege. Gender, Work & Organisation, 28(6), 2199–2215. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12731

WGEA. (2019). Higher education enrolments and graduate labour market statistics. https://www.wgea.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/august_2019_grad_factsheet_0.pdf

WGEA. (2025). Employer Gender Pay Gaps Report WGEA 2023-24 data release. Wgea.gov.au. https://www.wgea.gov.au/publications/employer-gender-pay-gaps-report